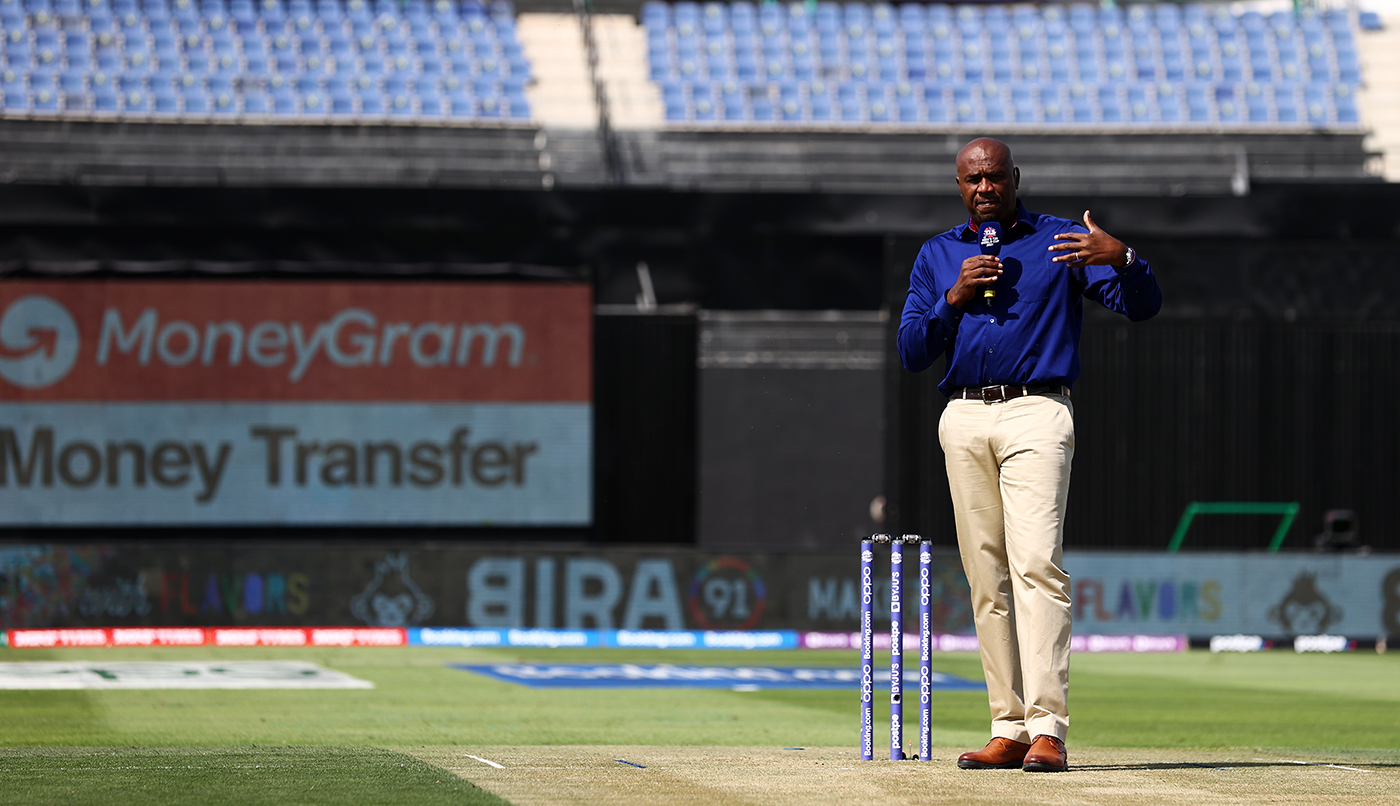

Ian Bishop on working as a commentator: 'If I don't research every player, I feel my work is unfinished'

After playing international cricket as a fast bowler for nine years, Ian Bishop started a second career in the game, this time behind the microphone. In this interview with a fellow commentator (albeit a non-playing one), Bishop talks about how he prepares for games, why discipline is important in the comm box, and whether he will one day open a school to teach commentary.I've heard veteran producers, broadcasters tell me: "There's no one better than Bish. Bish is the gold standard. Ian Bishop is what every commentator should be." Reflecting on where you are today in your broadcasting career, do you go to bed thinking, "I've done something right, I've got this"?I've spent a lot of time thinking about it over the last couple of weeks, and to be honest, I'm blessed to be in this position. It's not a position I desired to be in. I was blessed to be cast into it, I didn't seek it.And I'm thankful for the length of time that I've been involved in the industry with colleagues like yourself, and trying to grow every day.Just as I was as a player, [I'm] very intense with my job. My wife always said to me: "You never celebrated your success as a player. You get five wickets today, you're thinking, 'How I can get five wickets tomorrow?'" I've grown to satisfy myself and be comfortable in my own skin.I've been fortunate to work a little bit with you. Is it fair to say that you're actually a shy person, almost introverted, not comfortable being the centre of attention, which seems at odds with the nature of the job, being on camera and having to be in the public eye?I would say very, very accurate. Once I leave this environment, I'm happy to be in my room and not speak to anyone. The Covid pandemic was tough. People lost lives. [But] I've always said that the isolation part didn't bother me. I'm happiest when I'm in my own company, to the chagrin of my wife and children.But I think it is possible. You're speaking to one person or you're speaking to a camera. I'm not thinking too much about who is on the other side of the camera, so I'm comfortable with that.If I'm standing in front of ten people, that's a different story. If I'm in a room with people, introverts tend to think: how long before I can leave here? That's where I am.Play 01:26'I got into broadcasting indirectly because of Michael Holding'You've said previously that you never thought you'd be a broadcaster, that you thought you would be far away from the game once you were done playing. What changed?I have to be careful how I say this. Being in a group of people, especially people I'm not too familiar with, makes me uncomfortable. If I have to go out with anyone but my family, I have to prepare myself a couple hours before, thinking of questions and conversations I can start. I know that sounds weird to many people, but that's who I am. I've grown comfortable with that now at my age.When I retired from [playing] cricket, I wanted to get as far away from the game as possible because I didn't want to have to deal with sportsmen who were moody, with egos like myself.Whether it's by God's design or purely through coincidence, a friend of a friend of mine, who was a cricket and football agent, came to Trinidad. Channel 4 in England wanted someone for a West Indies tour in 2000. He asked me if I was interested because I was doing some radio in Trinidad at the time. I just cut a demo and gave it to him, and one thing followed the other. That's how it began internationally.When we're having this conversation, the levels you speak at are in contrast with when you're on air. For an introverted person, the biggest challenge would have been to articulate and modulate at broadcast standard?If it were left to me, I'd still be sort of that unbroadcast [voice]. But it would put people to sleep. I do put people to sleep anyway. But I had good teachers.The late Tony Cozier, just talking to him informally over and over, listening to him and working closely with him. One of the best, Michael Holding, was a mentor to me while I was still playing. I didn't know until about ten years later that he'd actually recommended me to Channel 4. They'd asked him if this Ian Bishop guy is a good person to get. He was at Sky. And apparently he said, yes, good guy, take him. And because Mikey's word is gold, they took that.Just listening to him [on air] - superb, superb. Less is more. Very calm. I don't know how that sits with this generation."It took me a while to understand that if there are two or three commentators and I'm not on lead and I'm in a second or third chair, I don't need to reach for the mic every ball"What are your principles of broadcasting? I think "less is more" is brilliant advice. And yet we also see that the landscape of broadcast is shifting. There are different instructions on different broadcasts because those in TV believe less is more is a dated concept. So from where it started to where it's now, how do you look at what is seen as the right way to broadcast? Or what is your way of broadcasting?There's no right way. There are different ways. Different people operate differently. It took me a while to be comfortable in who I wanted to be and how I wanted to broadcast. To find my own voice. Through much criticism, tears even, because of sometimes the way colleagues reacted or the public reacted.I learned at Channel 4 and TWI [Trans World International], which were good schools [to learn commentary at], to add to the pictures as opposed to radio, where you're painting everything. Coming out of cricket, I wasn't taught anything in broadcasting. So I got into television and sometimes I was just describing what was seen on the screen. And it took colleagues and senior directors and producers to say: add to the picture.If you hit the ball through extra cover, "Raunak drives one, from his great teachings with Coach Pandit back at university, through cover." It is a total waste of time as a commentator to say: "That's a good cover drive." There it goes through cover, the viewer can see that. So talking around it and adding to what I saw on the screen - I didn't understand what that concept meant, and through some harsh and hard lessons, I dug deeper into it.It came through colleagues in the comm box, through producers in your ear?Yes, senior commentators at the time. I would bounce a lot off Mikey informally, and he probably didn't know I was bouncing things off him. Back at Channel 4, a guy called Gary Francis, tough man. I thought it was a great learning school because it taught me that whatever is going to air has to be spotless, and we do it over and over and over until it is spotless. With TWI as well, we had a producer called Michael O'Dwyer, who seemed to have a photographic memory for everything and he would do the same.Have things changed?I think it's evolved. Different markets operate differently. In England, they want less. In the Caribbean, it's a little bit of a mixture, many people want less, many people want more talking. They say in Asia they want more activity, but some people here say, that's not my way. So adapting your commentary to different markets is a critical thing.Bishop with Sky colleagues (from left) Ian Ward, Mel Jones, Mark Butcher, Mike Atherton and Stuart Broad during an England-West Indies Test at Edgbaston in 2024 Stu Forster / © ECB/Getty ImagesHow do you stay authentic to how you think commentary should be? I'm sure when you come to India, there might be many occasions where you'd prefer silence to saying something.Yeah, IPL has a different tempo from Test cricket and from 50-over cricket and from an ICC tournament and a bilateral tournament. IPL is more up-tempo compared to an ICC tournament. It took me a while to understand that if there are two or three commentators and I'm not on lead and I'm in a second or third chair, I don't need to reach for the mic every ball. I'm happy sitting and making a contribution once every eight balls, once every over and a half, so you will never find me rushing for the mic, and that's who I am. It gives me a chance to scrutinise the game, but if I'm on lead then I have to involve my co-commentators while painting the picture, so that causes me to put out a few more words. After a day's commentary I'm tired. I'm gone straight to bed and the reason for that is I have to watch every ball. I cannot go away from a ball, so I'm concentrating as I was as a player for every ball.For a lot of us who may not be familiar with the intricacies of broadcasting, the lead commentator calls the ball, the colour or expert comes in after the action has been called and analyses it. Discipline is something you are big on in broadcast, but it doesn't seem to be as important to a lot of other people. When you're in the box, does that frustrate you at any time?Well, I've learned to understand that different people do different things. It's not that my way is the right way or the only way. I was taught kind of old-school. I'm older than most of the other guys around at the moment. I sat next to the late great Richie Benaud for about two to three years in the UK, picked up from that, picked up from others. In my own playing days I was all about discipline, my preparation, irrespective of what anybody else was doing. I was still the guy who would stay in his room, who wouldn't be out partying. That's my life as a Christian, so that travels with me in the commentary box.If I'm old enough to share one lesson to some young commentators coming through - and there's some really wonderful younger commentators coming through, including yourself - is that discipline of ensuring that the mic is down when you're not speaking. When you finish speaking, you put it down so the other person knows that it's now their turn.[And] involving the other members of that commentary panel. When you're leading cricket teams, the most important thing of being a captain or a coach is making sure the least member of your team feels he's as important as the greatest. And that's the same in the commentary box, so ensuring that everyone gets a voice."If I have to critique someone, there is [a] way that I can point out what you did wasn't the correct way to do it. Rather than saying: 'That is rubbish. You should be out of here'"Has that come because you have a sense of security about your job and there's no desire to compete in the comm box? And is that something you've seen is a challenge at times - that commentators compete, or aren't secure and therefore end up talking more, adding to the noise rather than adding to the pictures, as you said?I don't know. It's a hard one for me to answer because since I've been blessed to start the job, God has been kind and I've worked for a number of years, but even privately I'm never a person in my own social circle who will try to one-up someone to get what I want. That's not who I am, so it's not a "sense of security". It's who I've always been. But I'm very aware too of other people and making everyone around me feel lifted up.I had the great fortune of covering an India men's series with you in the Caribbean. And by some intelligent design, you were presenting and I was not! Not for a second did I feel like you were annoyed that you were asking me a question. I also remember when I was calling and you were on colour. As a Test match gets a little flat, you can talk a little bit more and just then Jomel Warrican got Shubman Gill caught at slip. You immediately called it and then put your hand on my knee and apologised [for interrupting]. You said, "Discipline, discipline."I don't remember those things, but if you're talking discipline, I beat myself up when I do that. Because your rule is your rule. That rule is important to you, and if I intervene on that rule, I lambast myself because just for half a second it takes away from what you're doing. And I hate doing that.I've heard this many times that if Benaud was commentating today, he wouldn't be a popular commentator or a good commentator. What do you feel when you hear that?I think no commentator is universally accepted. Richie was the one to point it out. When there was a vote for the best commentator and he won, he said: Don't worry about that. I didn't get all the votes. This person, this person, got some votes, so not everyone loved my style. And [there's a] part of the market that likes volume, they like words, they like high-pitched calling to excite them and there's another part of the market that likes calm. I think there would still be people who would cherish Richie, especially in Test cricket and 50-over cricket.Play 01:30'It took me a while to understand my own role'Could you pick a dream team of commentators you enjoy working with?No, I wouldn't answer that. Ajesh Ramachandran at the ICC [an executive producer] often tries to put commentators together who have synergy. I would point you out and say I enjoy working with you because you have discipline, you respect lines of demarcation, your calling, your colour. I would defer to you in certain circumstances, and your ego will not come out and you would defer to me.I love to listen to broadcasts when I can hear Raunak Kapoor is calling and he would say, "Simon Doull, you made a point two overs ago", "Cheteshwar Pujara, you said yesterday that this guy…" Referring to the other commentator and something he said and building him up so that that person suddenly feels, "Ah I did say something of value", it brings camera dream to the commentary box.If I identify anyone but you right now, then I'm going to forget a few names and my colleagues are going to look at me strangely the next time I walk into a commentary box. I think it would be unfair to call names.Let's talk about preparation. You tell stories of domestic Indian players on air. You go into detail with it. I'm sure many Indian cricket fans admire your level of research even after being in the industry for 25-odd years. I've heard that you also like to go to the ground, talk to the coach, watch training, talk to the curator. Tell me a little bit about what the Ian Bishop way to prepare for a day of broadcast looks like.I'm very thorough. When I dress, if my trouser isn't well-pressed or my shirt isn't well-ironed, my entire day is thrown off course. I kind of am a perfectionist with whatever I do. If I'm coming to do a tournament and I don't research every player and what they've done recently, I feel my work is unfinished. I feel dishevelled. I love research.If I wasn't doing cricket broadcasting, I wanted to be a teacher. When I went to do my Master's degree at Leicester in 2005-20006, I enjoyed research. It wasn't a chore."If I'm watching a game I've commentated on, I mute it. I don't want to hear it. You always think you can do something better, but I hate the sound of my own voice"My little girl is playing cricket now. She only picked it up 12 months ago. She loves it. She bowls and she bats left-handed, very unlike her dad. She didn't play at all and suddenly I got back home from last year's IPL and she wants to play. I said to my wife: let's give her everything she wants. We were taking her to practice sessions, and then I remember all these stories I've researched [about] these young kids and how much their parents have sacrificed, left jobs, sold pieces of property, sold jewellery, to put their kids through academies to give them a chance of making it. And I was complaining that I had to drive half an hour to drop her to practice every day.I think these stories must be told to encourage the next generation of parents who are thinking it's hard. The next generation of kids - you too can make it. And if it's a story of a middle-class family, same thing. This kid had all that they wanted, but they were still willing to work hard.I've seen you do it at the Under-19 tournaments with lesser known players, telling us their back stories.You have to. I know you do the same. There are a lot of commentators that do the same thing. We're telling stories. If we're not interested in the people, to me, the numbers lose some of [their] attractiveness.You said you'd be a teacher if you weren't a commentator. Part of a teacher's job is also to tell the kids when they're wrong, when they have done something bad. You have spoken about this before, about players being offended at something you said about them when you critique them. I have heard you talk about the importance of using the right words when you look to criticise. But is that getting tougher and tougher?Yeah, it's not recent. This has been going on before us.Bishop at the toss with captains Mahela Jayawardene and Daniel Vettori and match referee Chris Broad at the 2007 T20 World Cup Julian Herbert / © Getty ImagesDo you remember the first time a player came up to you and said: I didn't like what you said?No, I don't remember the first time. I remember one or two occasions where a former West Indian spinner came to a function. He said: "You're always saying things about me and why are you doing that?" And I said: "Bro, [your] behaviour in the field is not in keeping with what is expected for others to follow."So I have no problem saying it. But it took me a while to find that voice as well, as it will take everyone who gets into the game. More so for a former cricketer who has played with a lot of these guys.There's one young guy [in commentary] that I keep telling all the time: Don't beat yourself up. You don't want to criticise any of the guys because they are friends, but don't beat yourself up. You will grow into it and find your own voice in time.You can't fast-track that. It takes time. If I have to critique someone, I have to remember that their sister or brother or father or mother is watching, and there is some way that I can say, "Next time you can do this better" and still point out that what [they] did wasn't the correct way to do it. Rather than saying: "That is rubbish. You should be out of here. You should never come back." That's too caustic.I make plenty of mistakes. I would not want anyone speaking to me like that. Anyone that comes to me and puts their arm around my shoulder and says: "Bish, you didn't put in the work today. You didn't train. You didn't run. You didn't practise your outswing as much. And that's why you're going through this." I would listen to that tone. So I love Richie Richardson, the former West Indies captain. When I played under him, he would never shout at me but would always come and sit quietly and tell me what he wanted. And I listened to that.Is it not the role of the broadcaster or the commentator to also point out for the sake of the viewer that something that's happened on the field is poor? There are those that shoot straight. You mentioned Simon Doull. Back in the day, you had the Geoff Boycotts and Ian Chappells of the world, and they never held back. The world of cricket was quite black and white for them, and they commanded respect over a period of time. Do you sense that that is something commentators ought to be doing?I think every commentator is different. And the world of commentary needs that variety of voices, because the audience is a variety of audiences that require different things."It is a total waste of time as a commentator to say: 'Tthat's a good cover drive there.' It goes through cover, the viewer can see that"I think there are times now where you, unfortunately or fortunately, have to be careful about how caustic you are with people, from a broadcasting perspective. You don't want to turn off viewers as well. But you can't lie to the viewer and say "This is good" when it's bad. You might say it in a different way. And there are people in social media who always come and say, West Indies have lost this series. What have you got to say now? But you know West Indies have lost the series. You don't need me to tell you the West Indies have played badly. They lose the series, it's right there in front of you.So I think certain things are obvious. But the other voices who are a little bit more firm and forthright, I think they're needed as well. It's just a blend. Everybody has a voice.Do you go back and listen to yourself on commentary?No, I hate the sound. If I'm watching a game I've commentated on, I mute it. I don't want to hear it. You always think you can do something better, but I hate the sound of my own voice.How do memorable lines, lines in a big moment, high pressure, World Cup finals - when you call those, how do those come into your mind? Is there a process?Two ways I'll refer to. They are not the only ways but there are two options. I remember it was about 2016 when Ajesh Ramachandran, one of the great teachers of this broadcasting game, told us, formally: to always prepare.Many years ago, I would often find myself saying when a guy hits two runs and gets to his hundred: "There it is!" Ajesh said, no, tell us why that stroke or that hundred was important. Put it into the context of the match, his career, the decade, the team, and prepare yourself for the moment if you're on lead commentary before that comes up, so that you are able to paint that picture when it happens.Bishop at the 2023 IPL with Murali Kartik (left) and Anjum Chopra Arjun Singh / © BCCISimilarly, we were in Calcutta the day before the 2016 T20 World Cup final [and at a function someone] asked me who to look forward to in the game tomorrow. [The "Remember the name" line about Carlos Brathwaite came] on the night of that final based on the storytelling [from] the experience of the question that was thrown at me before.I find the wider I read, the more genres of entertainment I watch, the more news I consume, I'm able to put that into a story. It's good to prepare for it, but I don't like the fact that it's not spontaneous. I think spontaneity is the best filler of telling an event.A subject that's very close to my heart is the place of the non-player broadcaster. I know that a number of former players believe that the commentators' club should be a former players' club. What do you believe?People believe that? Really? I don't believe that for a moment. I believe that the professional [non-player] broadcaster brings a learning of life that players and former cricketers have not experienced because they have spent 25 years of their life almost in a bubble trying to perfect their craft, and there's nothing wrong with that. I can't go and play golf now and expect to be as good as a guy who's spent 25 years practising a golf game. It's very rare that that would happen. So the professional broadcaster brings insight, information, experience that he can bring into the game - the game will benefit. And of course the ex-cricketer brings something that maybe that professional broadcaster can never bring.You brought up the late Tony Cozier as one of your role models. Who better as an example?The best that there ever was.Since you desire to teach some day, would you ever care to open a school of broadcast and teach a thing or two of what you know?Once I finished my cricket career, [I did some] informal coaching. I spent a lot of time with guys like Denesh Ramdin and Ravi Rampaul. [I have been] around Dwayne Bravo since he was 12-13 years old. Sharing information with them, talking to them about life informally, and now learning from those same guys about the game is my best trait.I would love to teach, but I'll be a hard teacher. I think hard work is critical, critical, critical, but discipline [is important as well].When I go to do a women's tournament, I'm a guest in that environment, and I tend to try to be as inconspicuous as possible, but still be able to give something. If I'm [at a] youth tournament, I want everybody, including myself, to feel level.So if I'm going to teach, the greatest thing I enjoy in life is making that person feel a sense of value. But if I get disrespected - I've learned that over the last couple of weeks - that's the greatest thing in life I hate. When people disrespect me and try to make me feel less than, that fires me up.What happens when Bish loses his temper?If I'm at work, I tend to try to be in a corner or a different room to stay quiet. When I do get upset, it seems strange. I think it's blown out of proportion, because it's from one extreme to the next. I do not like disrespect, because I don't disrespect people.Raunak Kapoor is deputy editor (video) and lead presenter for ESPNcricinfo. @RaunakRK© ESPN Sports Media Ltd.